Instructor Eric Keller shares his advice for what to learn next after completing his popular Introduction to Maya workshop.

Introduction to Maya, by veteran VFX artist and instructor Eric Keller, funnels over two decades of experience into a beginner-level workshop. The comprehensive tutorial is a 15-hour journey through everything Autodesk's platform offers — and is consistently one of our most-watched workshops. Eric’s workshop puts Maya through its paces; he considers all aspects of the platform from both a birds-eye perspective and in close-up detail.

Introduction to Maya 2020 is a perfect starting point for those looking to get into Maya for the very first time. However, once the 15 hours are up and the final tip is shared, where should nascent artists go next? What projects should they take on, or how much should they practice what they have learned? For some, even working out what skills to hone in on, or identifying what excites them as an artist, can be a challenge.

We talked to Eric about where artists can go after they've finished his workshop. Read on and learn how to boost your Maya skills, manage self-expectation, and refine yourself as an artist.

Your first next steps? Practice. But practice what you love.

EK: The Maya workshop is intended as an overview in that it shows you the Maya interface and the tools but only gives a sense of the program's full capabilities. There's so much you can do in Maya and so many different features you might prefer over others. My suggestion is to hone in on those parts of the Maya workflow that excite you most. As soon as you finish the workshop, I recommend you take a few moments to think about your favorite parts — the parts that got you fired up and excited — and start a small project based on them.

Did you like modeling the most? Make a robot model similar to the drones or the quadbot featured in the series. Or perhaps animation was your thing. Take one of the models you've rigged from the series or even the example file, and create a short animation. Whatever you do, don't spend a million hours on it; it should be quick and fun, rather than perfect. Maybe set a goal of doing three or four 10-second shots, or model some robots and rig them to interact with the robots in the example scenes.

The purpose of this exercise is to reinforce what you have learned while it's fresh in your mind and in the context of a self-motivated project as opposed to repeating activities from the workshop. (Although that’s not a bad idea, either!) Performing these exercises — without striving for perfection, I should reiterate — will reinforce the connections in your brain and make it easier to work in Maya. Truth be told, this is all just practice, plain and simple, and it's just like learning a musical instrument.

But to go right back where we started: your practice should always focus on what you find fun. Don't just learn what you think employers will want you to know; pay attention to what you enjoy doing in Maya. (I don't believe any musician who made it to Carnegie Hall found playing their instrument a drag!) Follow your heart and do what excites you. Trust me. It will eventually lead you to unexpected places and help you discover what visual effects artist you're meant to be.

Practice regularly and stick to a schedule

Practice a little every day, rather than practicing a lot but sporadically. I've based this thinking on neuroscience. When you learn a new skill, you are literally making new connections in your brain, and those connections require reinforcement through repetition. It's like going to the gym, but instead of building up muscle, you're building on your brain. And, similarly to the gym, you'll see faster and better results by working 20 minutes every day for a week rather than working 140 minutes just one day a week.

I recommend spending 45 minutes a day in Maya if you can. Focus on just a few skills at first (the ones you love!), and don't try to learn everything at once.

Be patient. If life gets in the way of your practice schedule (it will!), don't feel discouraged and give up. Just work towards getting back on schedule. Remember, taking a break is always better than giving up!

Think about how skills overlap

Once you've finished the workshop, you've started practicing regularly, and you're becoming a little comfortable with Maya, try this exercise:

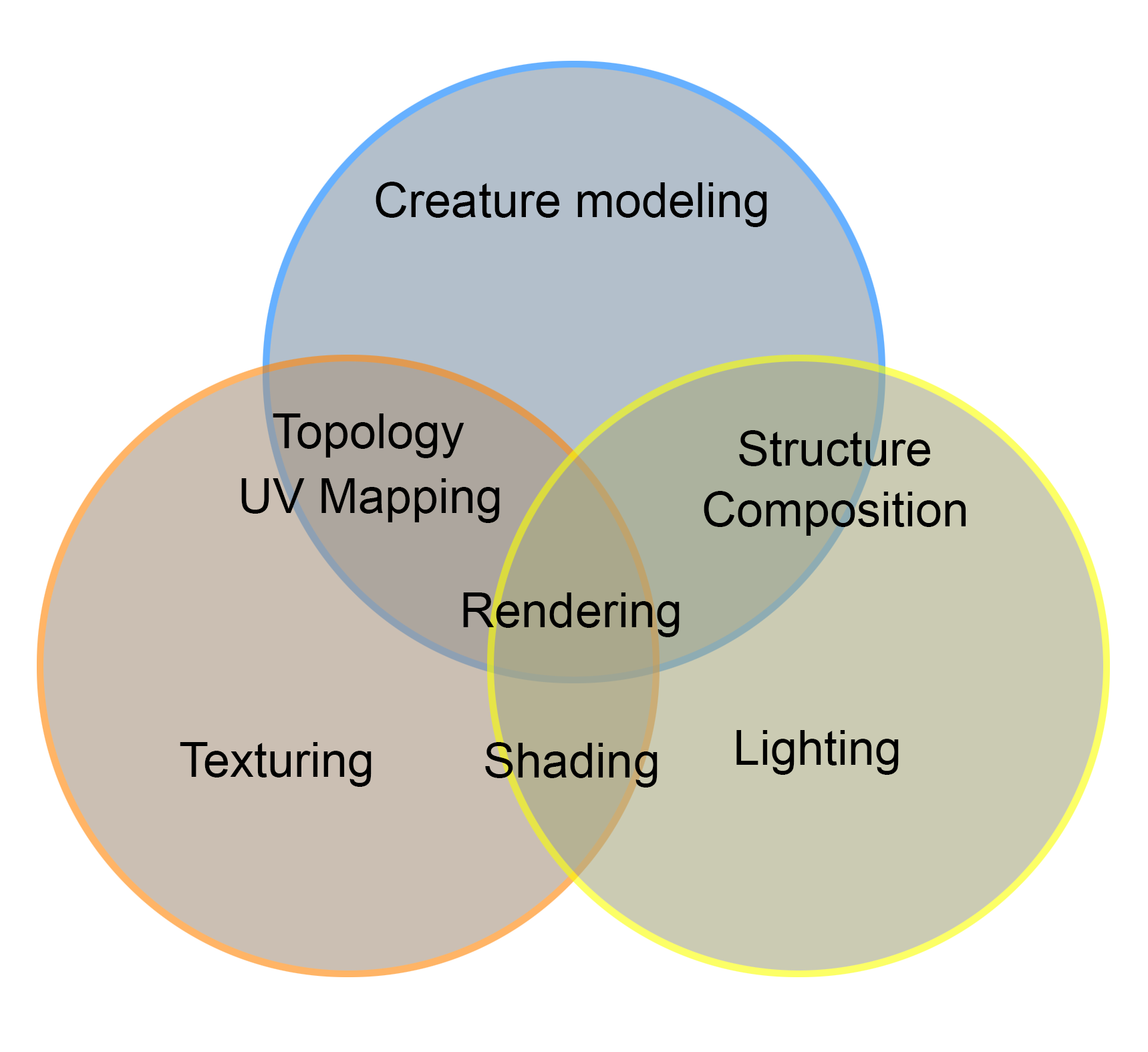

On a sheet of paper, write down the one thing you like the best. Let's say it's modeling.

Next, think about the secondary skills that complement the thing you like best, and write them down. For example, if you like modeling, you'll want to show off your models, right? Showing your models means you'll need to render them, and rendering them means you'll probably want to texture them and add cool details and surfaces. Texturing means you must learn how to create and layout UV texture coordinates for your model. You'll also need to learn basics like how to set up shaders using a rendering engine like Arnold, how to use a Maya camera, and how to composite renders in Photoshop. A lot comes from just wanting to show off a model!

After performing this exercise, you can take your notes and sketch out a Venn diagram with your favorite skill in the center and other aspects of Maya overlapping that skill. How much the skills overlap for you is probably a good indication of how much time you need to spend on each skill.

For example, when I performed this exercise, I knew I wanted to create cool poses for my models, but I didn't want to go full pelt into rigging. So, although the rigging skill overlapped my core interest in modeling just enough for me to learn what I needed to create poses, I certainly don't consider myself a master of rigging!

The bottom line is you want to create a general plan of attack for your learning but give yourself room to explore. In my case, although I originally wanted to be a character animator, I discovered there were so many other aspects of CG I enjoyed more than animation — particularly modeling, texturing, and rendering. But I couldn't (and you can't!) master it all; there's just too much to learn.

What you can do is find five or six skills that complement each other and get as good as you can at those skills. Doing so is a great way to find your place in the industry, and the results may surprise you. (It's been 20 years or so for me, and I still haven't got around to learning character animation!)

Do research — but not just about Maya

Books are a tremendous resource to further your learning, but not necessarily books solely about Maya. Software-specific books go out of date very quickly. (Trust me, I know; I've written a bunch of tutorial books, and they seem like relics now — some of the books I wrote on Maya several years ago are currently acting as a stand for my PlayStation. For this very reason, I shifted from writing books on software to recording video tutorials for The Gnomon Workshop.)

The books that don't date are those which cover core, fundamental art techniques. Consider reading books on cinematography, photography, color theory, painting, sculpting, traditional animation, and science. To obtain excellent output from Maya, you must have input—and that's where these kinds of books come in.

Here's a quick look at some areas you can look into to further the Maya skills you learn in my workshop:

- Character sculptors, riggers, and animators should learn anatomy. But Homo sapiens is only one species out of millions that live or have lived on this planet. If you're interested in creature work, you will need to branch out as life comes in many forms. Studying biology and natural history will help you here.

- Character designers and animators should study anatomy, acting, physics, and storytelling.

- Lighting, Look dev, and rendering artists should study photography, color theory, and painting.

- Previs artists, art directors, game design and virtual cinematographers should study storyboarding and concept art.

- Environment artists should study lighting, surfacing, architecture, and ecology.

- Rigging and effects artists should know how to write code, mathematical expressions, and some physics. Python is a great skill to have if you want to get into the more technical aspects of Maya. Personally, I'm comfortable with absolutely stinking at code, but I know some artists who work almost entirely within Maya's script editor!

However, allow me to contradict myself: it is important to resist being overly dogmatic about where you place your focus. If you're excited about getting into computer animation and visual effects, but you don't enjoy human anatomy or fluid dynamics, don't despair! The art form of visual effects offers many aspects and plenty of room to explore for people with different skills and interests.

Getting into visual effects is a yin-yang kind of thing: you want to balance the things you enjoy doing against the skills that will get you work. You don't want to generalize so much you're spread too thin, but you also don't want to specialize so much it makes it harder to find work.

I always suggest students start with the goal of being a generalist and gradually become more specialist as they get better and make more connections in the industry. Just be aware you will probably shift positions frequently throughout your career, so there's always going to be more to learn.

Explore your passions

Take up hobbies outside the realm of Maya, but make sure it's something you love doing. I've taken plenty of life drawing classes and a few painting and sculpture classes over the years. Although I gained lots of important information and skills from those classes, I found I wasn't excited by them. I wasn't excited because I wasn't passionate about those topics.

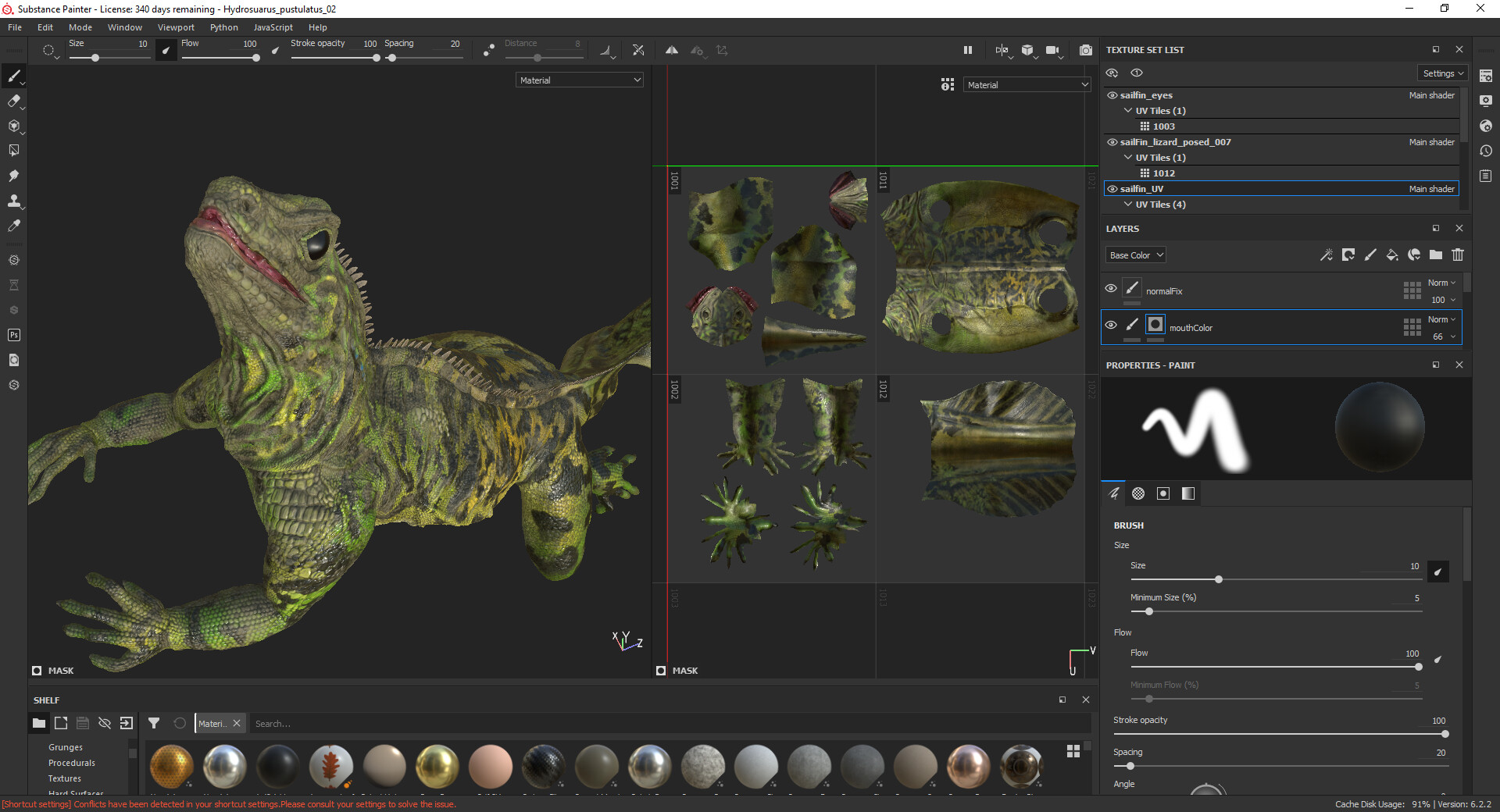

Things changed when I discovered macro photography. Macro photography empowered me to explore composition, lighting, and exposure in the natural setting I love. I learned I was much more interested in creatures and environments than I was in characters, which I did not anticipate when I first got into visual effects!

Also, as I enjoy lighting and rendering, I found macro photography related to what I wanted to do with visual effects much more than drawing or painting. Over time, I felt my CG art improved the more I practiced photography (and I built up a tremendous reference library I can access any time!). I gained these benefits because I loved photography as a hobby.

The key is to explore. Don't just study life drawing or painting because you've heard it’s what you "have" to do. Learning to become an artist isn’t at all like following a set recipe. If everyone learned art the same way, everyone's art would look exactly the same — and that would make for a pretty dull world! Instead, try a bunch of stuff and see what sticks. Your excitement will guide you toward the skills most useful for you. Listen to what your art is telling you about who you are.

Tip: I highly recommend life drawing and sculpting classes for anyone who's excited by modeling in Maya. Although I never mastered clay figure sculpture, I learned so much from John Brown's Gnomon Workshop videos and his in-person classes at the Gnomon School. The knowledge I gained from John's approach to the figure informs everything I do in ZBrush and Maya — even when I'm making a bug!

Get out there & meet people

It's crazy what you can learn to further your skills in Maya if you just go out into the world.

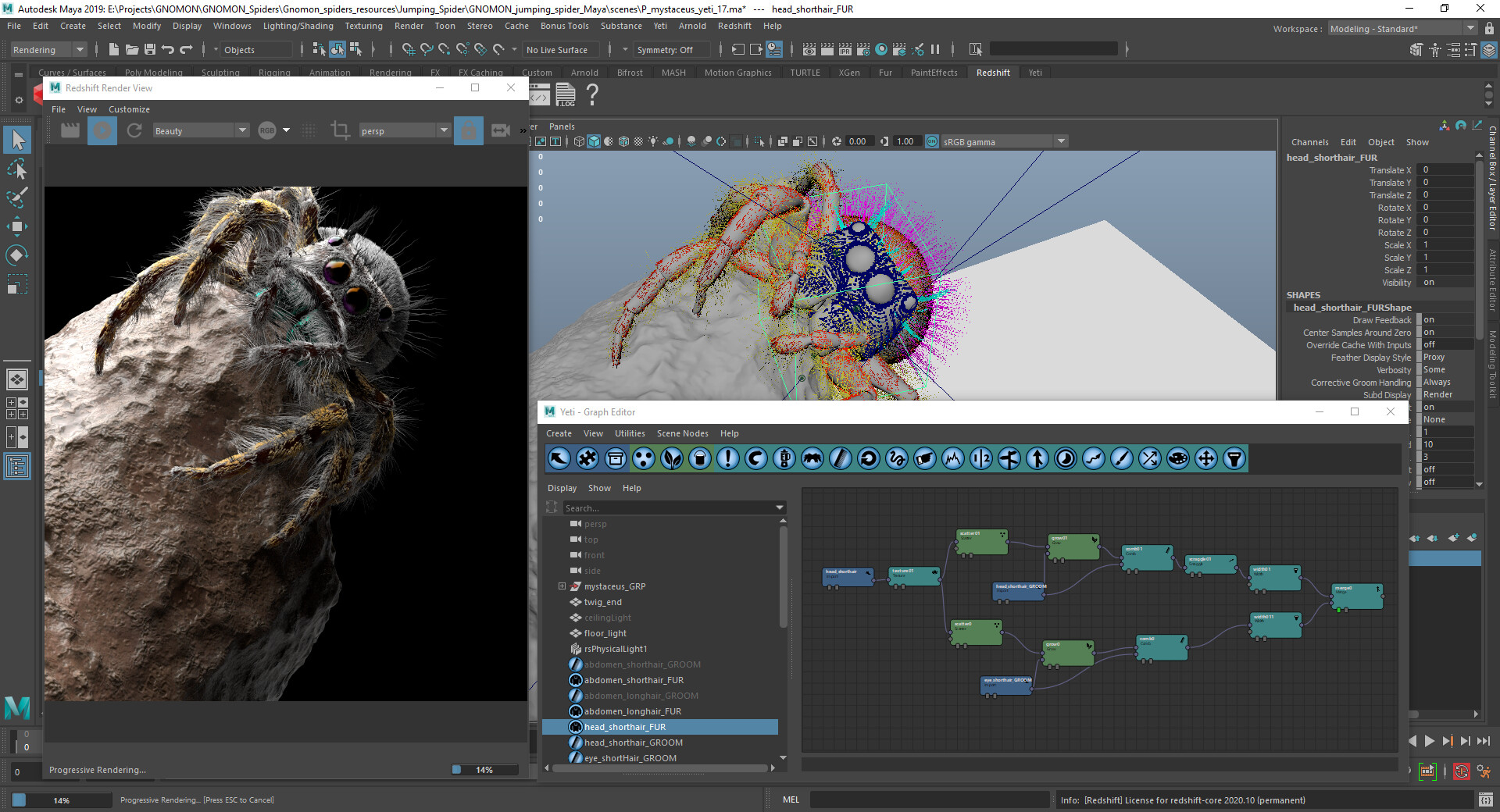

I found nature documentaries, especially BBC documentaries, a fantastic reference for acquiring animal facts and studying composition, lighting, and editing. I took that interest one step further by heading to zoos and museums. If you're also excited about creature design, I can't recommend doing this enough: Visit your local natural history museum, attend their events and even get to know the scientists who perform research. Such experts are more accessible than you may think, and most love nothing more than to talk about their research.

I know several leading researchers on spiders, ants, and flies, who are a massive help in my work. I can email these experts questions, and on more than a few occasions, they have taken me behind the scenes to view museum collections. I met many of them by just going to the Los Angeles Natural History museum and getting involved through events, classes, and volunteering.

Keep an eye on the future

The CG/visual effects industry goes through a significant technological revolution every five years or so, so you should always expect changes.

Right now, the most prominent technology on the horizon is real-time rendering in tools such as Unreal and Unity. Although modeling, texturing, and animation skills will remain in high demand for quite some time, the way we create shaders, lighting, and visual effects is changing drastically.

Furthermore, tools such as Quixel Megascans have made it much easier to create realistic natural environments. Learning how to use Megascans assets in traditional rendering and real-time rendering situations will be at the core of what environment artists, matte painters, previs animators, and look-dev artists do for at least the next 10 years.

Everyone is going to have to get comfortable with such upheavals; not just beginners. The point is: even when you've finished my Maya workshop, don't stop there. Keep an eye on the industry and where it's heading; pay attention to what new technologies are changing the game; and always — always — keep learning!

Related News

Beauty in the Beast: Neville Page on Burnout, Mindset & Creative Survival

May 07, 2025

Beauty, Beasts & Better Pipelines: Neville Page on Digital Design & Practical Makeup

May 07, 2025

Capturing Assets & Environments for Call of Duty: An Interview with Gui Rambelli

Feb 10, 2025